As with principles of judicial independence and secularism (separation of religion from the government), press freedom is not one of those ideals likely to stir the emotions of the masses, and yet it is absolutely a cornerstone of a truly free society.

That’s why it should be ringing alarm bells that Malaysia has fallen 18 rungs on Reporters Without Borders’ (RSF) annual press freedom index to a ranking of 119, sandwiched between the Republic of Congo and Nigeria.

RSF said that Malaysia’s press freedom situation improved dramatically after the 2018 general election, but things have gone in reverse since Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin took over, culminating in the recent “anti-fake news” emergency decree allowing the government to “impose its own version of the truth”.

But just why is it so important?

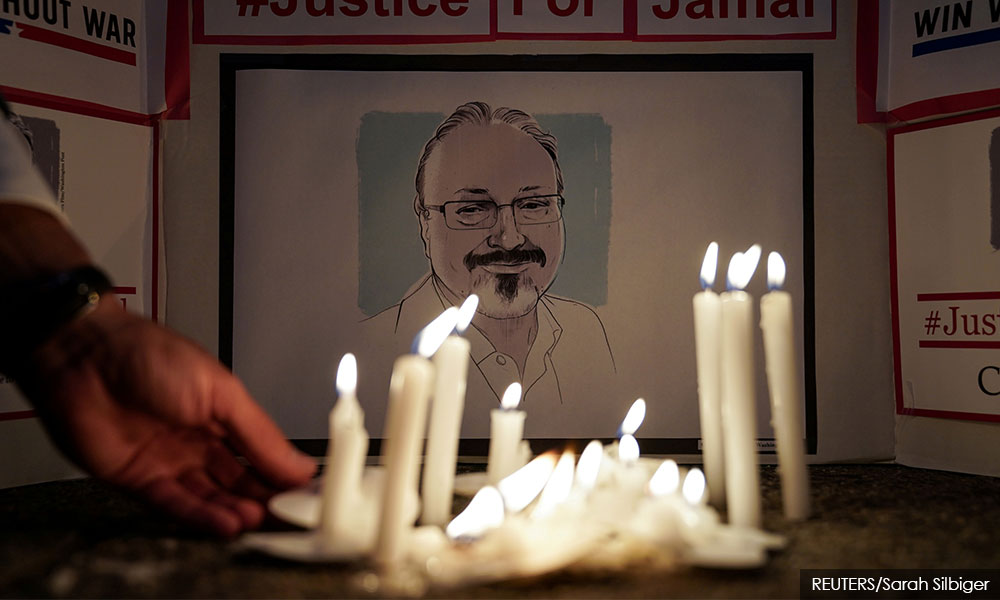

After all, Malaysian journalists are not being killed in a gruesome manner, like in consulates in Istanbul, where it happened to the ill-fated Jamal Khashoggi. Nor do we have cases such as the two Spanish journalists – David Beriain and Roberto Fraile – who were among those who died in an armed ambush in eastern Burkina Faso this week, while filming a documentary on anti-poaching efforts.

Indeed, the Committee to Protect Journalists reports that since 1992, at least 1,400 journalists around the world have been killed in the line of duty. Tens of thousands more have been attacked and harassed, jailed and intimidated in conditions considerably more harrowing than what we experience in Malaysia.

In October 2018, this reporter attended the World Editors Roundtable in Brussels, which featured a vigil honouring three dead journalists: Slovak writer Jan Kuciak, Bulgarian TV host Victoria Marinova and Daphne Caruana Galizia, a reporter from Malta. All three were investigative reporters exposing financial crimes and each of them was assassinated. And this, mind you, is in supposedly free and independent Europe just three years ago.

World Press Freedom Day itself has its origins in a Unesco conference in Windhoek in 1991. The event ended on May 3 with the adoption of the Windhoek Declaration for the development of a free, independent and pluralistic press – journalists around the world acting in solidarity to garner attention and support for a common cause.

Daphne Caruana Galizia

Daphne Caruana GaliziaPress freedom trends mirror corruption patterns

Centre for Independent Journalism executive director Wathshlah Naidu said that over the course of the last 30 years (and even further back), we can locate the development and challenges related to press freedom in the context of the evolving nature of human rights and democracy, including in situations of internal armed conflict, civil unrest, political turmoil or situations where legal and institutional guarantees of human rights are circumscribed to a large degree.

“The trends on press freedom also mirror patterns of systemic corruption and institutional impunity.

“The Covid-19 pandemic has also contributed to the complexities in protecting press freedom in most countries as it is often used to justify restrictions and clampdown on media,” she told Malaysiakini.

Wathshlah said the struggles of the last 30 years remain as we continue to see killings, attacks, threats and harassment of journalists and their sources.

“In worst-case scenarios, these have included bombings, shootings, summary executions, death threats, torture of journalists to reveal sources of information, beatings of journalists and photographers covering protests or other civil unrests or enforced disappearances of journalists.

“This is often accompanied by the use of repressive laws by authorities in a number of countries to silence and/or suppress independent media and to take punitive actions against journalists and media outlets, often without a legitimate basis or is disproportionate, including through compromised judicial proceedings,” Wathshlah added.

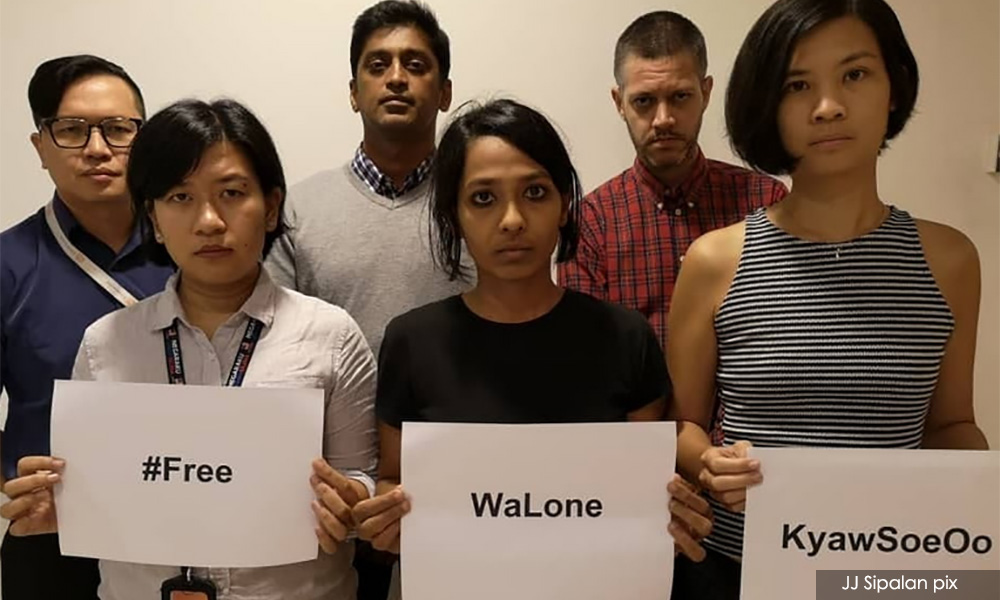

This can be witnessed in the neighbouring military dictatorships of Thailand and Myanmar, in which repressive regimes impose bans, searches, seizure of equipment and publications, the closure of radio and TV stations, enact severe restrictions on access to the internet and carry out surveillance of media premises.

When journalists are murdered with impunity

Mexico, with its infamous drug cartels, is considered to be among the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists to work in. Journalists exposing financial scandals and environmental abuses are particularly targeted, while Covid-19 has also provided incompetent and corrupt governments with a greater need to cover up.

In Egypt, President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi banned the publication of any pandemic statistics that didn’t come from the Health Ministry. In Zimbabwe, investigative reporter Hopewell Chin’ono was arrested shortly after helping to expose the overbilling practices of a medical equipment supply company.

China, incidentally, is still firmly anchored among the Index’s worst countries, ranking 177 out of the 180 assessed by RSF, which said that the country “continues to take internet censorship, surveillance and propaganda to unprecedented levels”.

One of the most prominent recent cases includes that of Jamal Khashoggi, a dissident journalist who was murdered. His physical killers were punished, but the man implicated as being behind it remains untouched.

“The reported speculation that the killing of Khashoggi involved the crown prince of Saudi Arabia raises the possibilities that impunity continues to prevail. Questions remain on who authorised the operation and inter alia the killing,” Wathshlah said.

She highlighted that the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, Agnes Callamard, initiated an inquiry and traced the chronology of events that led to the execution of Khashoggi and analysed the evidence and applicable international laws.

“Callamard’s report made the case for state responsibility of Saudi Arabia, not just for the violation of the right to life, but also for the lack of proper investigation and lack of transparency of the legal proceedings in Saudi Arabia against the alleged perpetrators.

“Aside from the findings in the special rapporteurs’ report and related statements by the UN, this case has clearly highlighted the extra-territorial nature of threats against journalists and the lack of protection in this context.

“It also spotlights the increasing repression of journalists and failure of early and proactive warning systems, as well as the lack of commitments of the states in fulfilling the international legal obligations and commitments to freedom of expression and speech,” Wathshlah added.

Women reporting on gender issues also vulnerable

As a feminist, Wathshlah often considers the gendered cost of reporting for a woman.

It’s clear that aside from the prevailing gender-based discrimination and stereotypes, women reporting on gender-based issues are often at a greater risk of harassment and violence, she said.

“Over the course of the last few decades, a number of women journalists have been killed for their reporting on gender, where it is often seen to be challenging patriarchal and misogynistic cultures and traditions.

“Many other women journalists have also been targeted and they suffer gender-based violence, both online and offline, on the basis of their gender and other related work.

“According to Unesco’s statistics, 114 women have been killed since 1993. Four women journalists were killed in 2020, while another four women journalists were killed in the first four months of 2021,” Wathshlah said.

She named a few of the women journalists killed: Betty Barasa (Kenya), Malalai Maiwand (Afghanistan), Maria Elena Ferral (Mexico), Teresa Aracely Alococer (Mexico), Nawras al-Nuami (Iraq), Gauri Lankesh (India) and Miroslava Breach (Mexico).

“These women are to be remembered and commemorated for their commitment to journalism and work in media, despite the challenging environment and prevailing attacks,” she added.

Malaysia on a slippery slope

Given all that is happening, just how bad has it been for Malaysia to have fallen the most spots in the world ranking?

Wathshlah believes Malaysia is sliding down a rather slippery path.

“The window of opening we experienced during the Pakatan Harapan period for a more free and safe space for media to function independently is slowly shrinking.

“Firstly, the political turmoil since the Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition took power in March 2020 has acted as barriers to the media taking on its role independently.

“Second, there is an ongoing crackdown on media for their reporting, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Lastly, laws that stifle press freedom are still in place and are being used against journalists and media agencies,” she said.

All these culminated in a State of Emergency, which was proclaimed on Jan 11, 2021, and then on March 11, Muhyiddin’s government gazetted an ordinance supposedly to combat “fake news” relating to Covid-19 or the emergency proclamation – but which in reality gives his government sweeping powers with grave implications for press freedom.

The Emergency (Essential Powers) (No 2) Ordinance 2021 states that perpetrators who spread “fake news” in writing, videos, audio recordings or in any other forms that may convey “words or ideas” will face action.

The ordinance grants the court powers to order the removal of a publication if it is determined to be “fake news”, failing which, the court may order the police or an authorised officer to do so.

The ordinance also overrides the Evidence Act 1950 and gives the police the powers to arrest, enforce, investigate and inspect.

“Journalists and media organisations have found themselves under heightened scrutiny as more among them end up being investigated by the police, and even charged with criminal offences because of their reporting,” Wathshlah said.

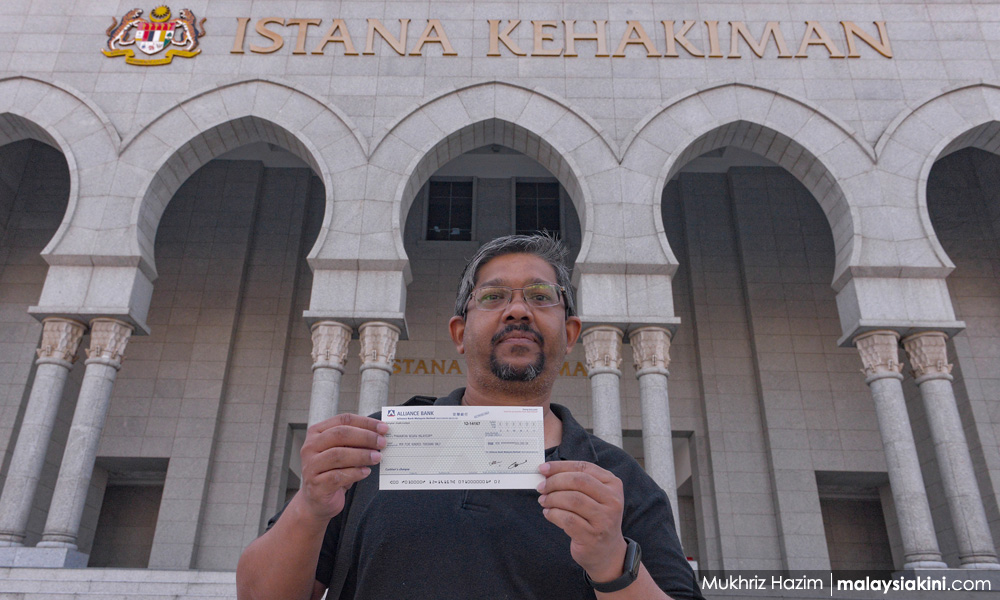

She cited that earlier this year, Malaysiakini was fined RM500,000 by the Federal Court for contempt of court, over readers’ comments on its article about Malaysian courts reopening after the Covid-19 lockdown.

“Last year, we saw several journalists and media agencies investigated, harassed and subjected to legal action by the state for their critical reporting or dissenting views.

“These cases include that of blogger Dian Abdullah, Channel News Asia Malaysia Bureau chief Melissa Goh, South China Morning Post (SCMP) correspondent Tashny Sukumaran, CodeBlue editor-in-chief Boo Su-Lyn, Malaysiakini and its editor-in-chief Stevan Gan, Gerakbudaya and the authors of Rebirth, Al Jazeera, Astro and UnifiTV.

“This list does not include the numerous instances of online harassment by government ministers against journalists who allegedly misreported the news. Read together, these can be seen as a deliberate and concerted series of actions intended to stifle media freedom,” she said.

She pointed out that even before the ordinance, various repressive and archaic laws were still being used against the media and journalists. These laws include Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia (CMA) Act 1998, the Sedition Act 1948, Sections 504 and 505 of the Penal Code and the Printing Presses and Publications (PPPA) Act 1984. Other laws include Section 203A of the Penal Code and Section 114A of the Evidence Act 1950.

“Malaysia’s drop in the world press freedom index also signifies that the current government may have been successful in its intimidation and fear tactics that are now possibly contributing to an environment where the media is more suppressed and less inclined to be overly critical and expected to toe the line when it comes to reporting,” she added.

“Malaysia, within the larger global context, may not seem as restrictive or the environment for media as precarious, but if this pattern remains, we are then at the risk that the government will continue to undermine and threaten media freedom in Malaysia.

“We will have to act now so that we do not join the ranks of the countries with a history of journalists being killed, tortured or having disappeared.”

Is press freedom still a niche issue?

When Malaysiakini was hit with its massive and potentially crippling fine, ordinary Malaysians bandied together in record time to drum up the funds to help us pay it. This would seem to indicate that while press freedom gatherings and protests do not have the numbers of, say, a Bersih protest, there is a strong understanding among the public of the importance of free and independent media.

“A democratic nation must ensure freedom for journalists to carry out their duties in delivering news and freedom for the public to gain access to accurate, reliable and timely information.

“When the media can perform their duties without fear and favour, the public will definitely obtain information that is accurate and unbiased. This is our means of ensuring effective scrutiny and holding the government accountable to people through operative good governance and rule of law.

“This understanding and message are, however, not as clearly articulated or transmitted to the people on the ground. We need to be more strategic in communicating the importance so that the masses are able to relate to the fundamental importance of the role of free and independent media,” Wathshlah said.

One wonders, too, why some journalists are so fearless. Surely, volunteering to do exposé on Mexico’s drug cartels or covering ISIS is a possible death sentence – yet they do it at risks to their lives.

Wathshlah added: “Those passionate about and committed to being agents of social change and reform will continue the struggles for reform and influence social change by attempting to dismantle the established power structures and speaking up, even in the most restrictive environment or in the context of an authoritarian regime.

“I continue to see this now in the commitment of my fellow activists in Myanmar, who are resilient in their fight even in the midst of the most blatant crackdown and at the risk of being killed.

“This level of commitment is also evident in the journalists who are continuing to report on the development in Myanmar from within the country. If journalists are to adopt and live by what we understand as the role of media – to seek and gather information, write the news, disseminate the news in a balanced and ethical manner – this goes beyond investigating and reporting on current events or updating the general public.”

Source: Malaysiakini